… and so I found myself making the six hour drive, which felt like an odyssey, the dark mountains reflecting my anxious state. As I sped down the road after dusk, the dark country roads off the highway, shining my brights on and off, and barely dodging a deer in the process, an almost serendipious avoidance of it, as shortly before I saw the creature I thought to myself that hitting an animal right now would be the worst thing that could happen. When I had this thought I shined brights to see better, and immediately, there were two in front of me, one crossing the road, and the other on the curb. I slammed on the brakes as quickly as possible, holding the steering wheel straight, aware it would be better for my safety to hit it straight on, then spin out. Thankfully, the deer moved forward, giving me just enough room to spin the wheel to the right, and I continued my journey through the mountains, and off the highway into a region I had never been to.

I. a walk

The surface of my anxiety was a recent argument that erupted unexpectedly during a date, which, needless to say, ended at the same tempo as the argument. I couldn't make out or remember what led to the sudden shift in mood, and kept analyzing it in my head. But that was just the feeling’s surface, like a thin plate of glass, covering the source.

If you look at the glass you see your reflection in it and find yourself in a feedback loop, a loop where the internal monologue takes on unexpected twists and turns, the brain organizing conflicts like a puzzle, believing that the more it thinks about it, the more likely it will solve the conflict and finally arrive at something resembling peace. Yet all modern research tells us the opposite. It is only from accepting anxiety and depression, that the "disorder" (I can't think of a better word for it) fades into the background. Yet the brain wants to be a hero of sorts, and convinces us to continue looking at the reflection, thinking it will somehow battle away our anxieties by staring at them.

Another option is to look at the water underneath the glass, and dive into that dark texture. This is something akin to classical psychoanalysis. Its very helpful if done at times, but often the best option is just to look away; let the ice melt at its own pace, and the water become less murky over time. But before this metaphor moves away from me, I want to get to what was in that dark swamp, get to the elephant in the room (not to mix metaphors); and that elephant of course is war.

The Wallowa Lake and all its trails are in Joseph, Oregon, and days after the drive, after finally completing the job I came for, recording an audiobook, spending days on end hearing the writer speak and taking notes on words and phrases, I finally was able to take the walk I had been dreaming about all week. As I ascended the snowy switchbacks, my feet sometimes sinking inches into the ground, the view of the lake, which was completely frozen over, looked more and more unreal, and the mountains surrounding the lake became more majestic, the height grand enough to see the tops eye to eye. I passed barely anyone on the walk (three people in four hours), and was completely alone at the summit, and I did weird things one only does in total privacy, such as spin around with my arms out, say hello to a tree, and sit on a rock to breathe and meditate (okay, maybe that last one isn't so weird). That day, I didn't realize that Wallowa Lake was created by a falling glacier, which cut a canyon into the mountainsides; nor did I know that the lake, which looks almost human made, as if from a dam, is so deep that they there are spots where they have never hit the bottom, that it is in fact one of the deepest lakes in North America. It is for these reasons that it is considered one of "Oregons Seven Natural Wonders”. Wonder is a good word for Wallowa. To my eyes, seeing it frozen, it looked like something out of a childhood dream, a winter wonderland, or a hand drawn fairy tale.

Perhaps it was this gentle reminder of childhood that gave the region such a noticeable and strong energy; but I honestly believe that energy came from somewhere else. I had been feeling an environmental energy since I arrived, when my anxiety slipped off organically without notice, revealing the calm underneath it, as if this region was a spa for the soul. It felt spiritual in a way I have only encountered in a few places on my travels, Hawaii being the most similar, and like those islands, I was keenly aware that this was sacred land, a land filled with spirits that seemed to softly walk around the trees.

Even the name of the town is sacred, it being named after Chief Joseph, of the Nez Pearce tribe, who fought to defend his home from the United States, a "democracy" that at the time was also engaged in an imperialist expansionism both violent and barbaric, an imperialism smudged over by the centuries of history, and of course by old shows and cinema portraying the white settlers as heroes. But even the word "settlers" implies a violence.

Our country advanced into what would have been the equivalent of another country, in a blatant and noxious power grab, demanding the other citizens to naively accept. Chief Joseph was the leader of a tribe that outright refused to sell or to give up, and his resistance to the United States army not only earned respect from various military officials, leaders, and officers, who admired his bravery, leadership, and tactics, but it eventually made him a cultural celebrity throughout the entire country. Newspaper articles would romanticize his tribe's resistance, even though these papers were printed in the country that was taking the land. It must have been stingingly ironic for the aristocrats to exoticize the defending army, as they subconsciously supported and benefited from its invasion.

Yet this admiration was indeed warranted -- the Nez Pearce slowed down the advance of a nation that should have easily overwhelmed them, what with the sheer manpower, the capital budget and of course the technology; which just like today, was adapted first and foremost by militaries; no matter how utopic a technological idea is, it eventually becomes weaponized, back then with things such as machine guns (invented by someone who wanted deaths to be more "humane", and based on early telescopes), and today with so called 'cyber warfare', something that Russia is a master of using. And its of course impossible to think about Chief Joseph's resistance, and not be reminded that it is a distorted fun house mirror of exactly what is happening today. This reminder gives one a double feeling, one of cultural guilt for being part of a violent history, and one of sympathy for both Ukraine and for the Native tribes -- hearing either story makes the other ring out louder.

As the US army encroached on Oregon, and as it became more and more clear that defeat was eminent, Chief Joseph adjusted his strategy to that of escape, aiming toward Canada, a country that took in other refugees in at the time. Unfortunately, despite valiantly fighting, despite slowing the US army down significantly, Chief Joseph was eventually captured by General Sherman, illegally during a cease fire no less, and only 40 miles south of the Canadian border. And just as Zelenski is becoming something of a cultural hero to many Americans and Western Europeans, Chief Joseph spent the rest of his life in newspapers, in parades, in government offices, trying desperately to advance the case for his tribe and for Natives in general.

Yet despite the history that surrounds these mountains, for most of my walk my mind was in a blank slate, similar to the snow. I didn't reflect on war, nor on the anxiety and tears from the endless news stories, each one surprising me with its devastating emotion; for example, the old lady who gave a Russian soldier a packet of flower seeds, saying that when he falls dead, the seeds will spread across the land; or the mothers in Poland who left dozens of baby strollers outside train stations, so that citizens fleeing the country would have a place to put their babies in when they arrived. These stories, of which there are so many they are unending, are hard to take it, possibly because they are not only painful, but also blazingly human.

Its easy to see our reflection in Ukraine, which shares with our country common definitions and terms such as “democracy”, “first world”, European, globalized, etc and so on.

I'm not going to get into the morality or accuracy of those terms; but I have been surprised at a few leftists who don't seem to understand the heightened emotions I feel about this war, or who react to this war by wondering where the outrage was at other ones. At first I couldn’t tell if these people were emotionally cold, or the opposite -- so emotionally warm and empathetic, that they've become used to this feeling of sadness, that reading about any history does the same to their hearts as seeing an Instagram video taken just hours ago of a building in ruins. That for some, they see themselves not only in Ukrainians, but in Palestine, in Iraq, in Afghanistan. The world has been embroiled in wars since I've been alive, and for all of modern and ancient history. And yet, I think the emotional shock of this one goes beyond the faces in the videos and photos, beyond the visceral sadness of seeing instant human suffering in the palms of our hands.

It also points to something else -- an awareness that our very fabric of so called modern society is coming unglued and undone, at a faster pace than we expected (It was hinted at with Trump’s election and Brexit, among other things).

People my age and younger took for granted that we've been living in a post Cold War world, a world taking place after the fall of the Berlin Wall, in a time of first world peace. Though all the wars we’ve lived through are appalling and inhumane, its also true that those wars seemed psychically distant from us in ways we didn’t realize, violence happening in places we don’t tend to travel to, in places we don’t have friends or family members at, or know someone with friends or family members at. This might be the first war of our generation that represents the idea that progress could be only temporary; some kind of fluke; just as Trump's election represented a similar thing, albeit in a different way.

In other words, it hints that the unprecedented peace our world has been in, for the globe is actually in one of its least violent moments in all of human history, a fact that easily gets lost in the news storm, which like any programming, needs to be entertaining to make income -- that this peace is just a tiny thread, able to come apart and unravel at any moment, and in fact is unraveling before our very eyes.

This visceral tearing apart which we are all reacting to consciously or subconsciously (and after finally accepting the new reality of the pandemic) has upended me and my thoughts, bleeding into relationships, and spilling into an argument at an otherwise nice date, spilling into loops in my head while making a long drive, off the highway and into something approaching wilderness.

It has also unspooled my normal mental obsessions; which since 2016 have namely been the definition of and changing terms of a shared reality. In fact, the original draft of this issue, made before the invasion, was about the mixture of reality and fiction, and explored two books and movies that combined those genres; including a visceral book about torture in Chile. The sometimes apocalyptic writings of that issue seem almost "quaint" to me today, during this small but defining stamp in time.

The audiobook I recorded last week was written by a self published writer, a lifelong cowboy and rancher who began incorporating radical approaches to soil regeneration, and who is perhaps one of the more sincere utopists I have ever met. Though he grew up identifying as a Republican, and was even a friend of Dick Cheney's, he hasn't voted that way since the 1980s; and left his home of Wyoming to find a place more open to his ideas. This cowboy sincerely believes that ranchers can change the world, can mitigate climate change, through the simple practices of how they let cows graze. He believes it to be a personal responsibility of theirs — and his work has had surprising results. In a period of 10 years on one plot of land, he's seen native grasses increase nearly 200% while invasive ones decreased almost the same number.

It is refreshing to hear such optimism, especially during pessimistic times, and it feels clearing when faced with it. It is my belief that pessimism plays into the hands of people like Putin or Trump; but more severely, it plays into the hands of the systems of power which count on our passivity, a power which we take for granted, but which in fact are invented by us and can therefor be destroyed by us as well.

These systems are not a part of nature; but rather of the mind, a mind which turns quiet as I sit on top of a rock on a mountain, light bouncing off the snow and hitting my skin, a tree in the distance standing alone, my body feeling the sensations of stillness, and wind moving through my ears which they interpret as "silence" -- even though it is anything but. Silence is something like life. When one is in a quiet place, the quiet becomes like a raging river, pulsating with energy and harmony. It is something that John Cage considered to be musical. If one can feel it, can listen to it, then there is a power in there similar to transformation.

It is a like a bath, the noise of the quiet yet piercing wind.

As I begin my descent toward my car, I attempt to take and carry this silence home with me, and remind myself that there are parts of the earth that still feel untouched, as wild as the deer I almost hit, when I had to slam my brakes on the journey, move my car like a tango. The whole thing happened in one quick breath, or heartbeat, as many important events do, though this event was thankfully gifted to not be important, the best events in life are not important, nor are they earth shattering, the best moments are non-events actually; and though the deer has no borders or economics, no systems of thought, it still must have felt a similar fear upon seeing my car, which probably looked like some form of terrifying monster; as a human in Ukraine feels hearing sirens in the background or seeing military caravans approach; and I imagine that the deer wasn't separated from its companion, the one that froze while the other moved. I imagine they both crossed the highway, as I sped away, right after sunset, my headlights shining on its clear, furry skin.

****

end of walk.

***

Part II : Inventory

Books

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamin Labatut. Chile. 2021 (Translated. 2020 Original). 4 1/2 stars.

Incredible, apocalpytic, and magical book disguised as science essays which are in turn disguised as fiction. Each "essay/story" hybrid, all about scientific discoveries, invents more fictional aspects as the book progresses. The fictional aspects stay in the biographical details, however — the discoveries are real. Centered around physics and mathematics, the themes are how these findings were either used for war, or how discoveries drove their creators existentially mad, by pointing out how absurd the universe is.

Like a hybrid between two of my favorite writers -- Borges and Sebald. And though this isn't as good as those two, I haven't read anyone else do this kind of hybrid, even as fictional essays become more common in South American literature. (And if you can't yet tell, this is the kind of writing that inspires me. That and “auto fiction” which is such a dumb term).

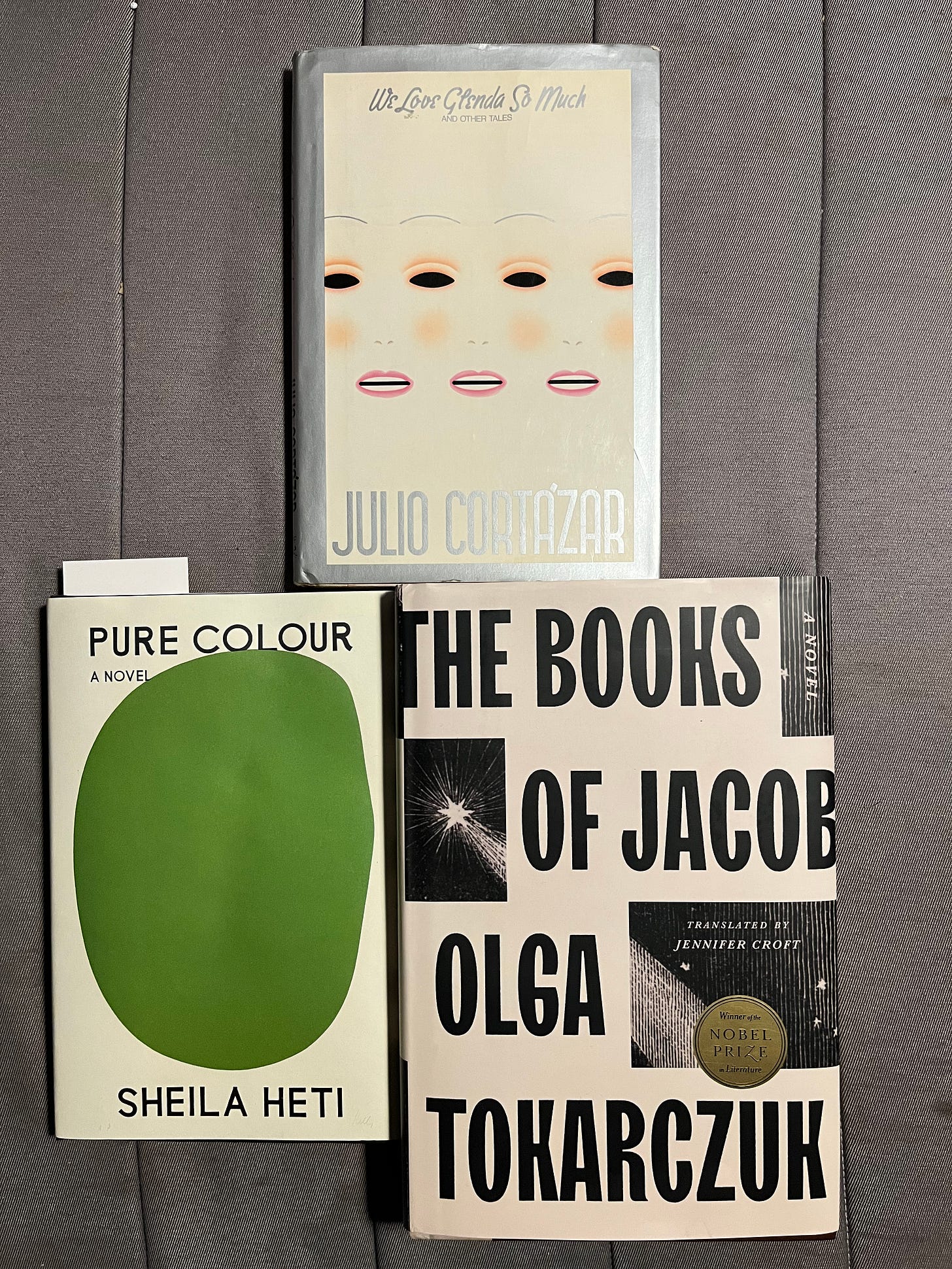

Currently reading: Cortazar, Tokarczuk, Sheila Heti, and Ocean Vuong

MUSIC

On heavy rotation, in my record player is the following:

Hania Rani - Esja (2019) :

gorgeous instrumental piano

Vikingur Olafsson - Dubussy / Rameau :

I’m on classical music kick & this is one of three Debussy albums I’ve picked up this winter. The other two are just as good though. Really love piano music right now.

Bill Evans Trio - Waltz for Debby (1962) :

Also on a jazz kick. Bill Evans reminds me a bit of Debussy and Satie, actually.

Don Cherry - Complete Communion (1966):

This is more “out there” / cosmic jazz. Less melodic, but very inspiring.

Stereolab - Mars Audiac Quintet (1994)

Stereolab - Transient Random Noise-bursts with Announcements (1993)

I mainly listen to instrumental at home, to help relax. But when I listen to “rock” — its mainly only been Stereolab !

PJ Harvey - Is this Desire? (1998)

On my drive to and from Joseph, I listened to *a lot* of PJ Harvey. This is one of two LPs of hers I own. My favorite is “To Bring You My Love,” which might be one of my favorite 90s records in general. Spooky/industrial/psychedelic/driving music. But Is This Desire is also great and has a song that reminds me of In Rainbows.

FILMS

I will return to this section on issue three -- as this writing became much larger and longer than I had intented.

III. appendix:

(a strangely optimistic journal entry written a few days after the first draft of this)

I love jazz music and reading and the long rolling grey mornings of Portland, weekend mornings with coffee and soft, unbearably soft daylight reaching in through my windows to illuminate everything underneath me, the wor4ds on the page, the pen in my hand, the book that stares at me with its sense of gravity and levity, the steam rising from the coffee cup which visually looks like the aroma of the strong beans, roasted here in the city, which I am able to press down in a plastic contraption that makes a fake but delicious version of espresso. I am aware, even as teh world is falling apart, of my incredible fortune to have a roof over head, and a morning such as this. A morning filled with peace. The kind of peace where the soul can explore, can grow, and can play.

This is issue two: my goal is to publish these around the 1st and 15th of each month; but I’ve yet to hit that mark. I hope you enjoy. Please spread the word if you do.

All writings and photos are copyright 2022 by Nate Wey.